The Ultimate Guide to Ethiopian Injera and Wat from a Chef Who’s Cooked It All

The first time I made injera and wat in a professional kitchen, I knew I was working with something special. These aren’t just recipes—they’re cultural experiences. Injera, the soft, spongy flatbread, becomes your plate, your utensil, your foundation. Wat, the fiery and aromatic stew that goes with it, is comfort food at its most vibrant. Over the years, I’ve made countless batches for events, restaurants, and home dinners. In this guide, I’ll take you deep into both dishes—how to prepare them traditionally and how to adapt them for modern kitchens. No fluff, just real advice from someone who’s cooked Ethiopian food by hand, by instinct, and by practice.

- What Is Injera and Wat?

- Essential Ingredients for Authentic Flavor

- Fermenting the Perfect Injera Batter

- Traditional Cooking Timeline (with Prep & Rest)

- My Favorite Wat Variations: Meat, Lentils, and Beyond

- Slow Cooking Wat for Deep Flavor

- Cooking Injera on Different Surfaces

- Vegetarian and Vegan Meal Options with Injera

- Drink and Dessert Pairings for Injera and Wat

- Storing and Reheating Injera and Wat

- The Texture Science Behind Injera

- Ethiopian Dining Etiquette and Cultural Context

- Common Mistakes I’ve Learned to Avoid (So You Don’t Have To)

- Beginner Tips: Your First Injera and Wat Made Simple

- Fusion Flavors: Creative Takes That Still Respect Tradition

- Cooking Method Comparison: What Works Best

- What’s the difference between teff injera and mixed-flour injera?

- FAQ

What Is Injera and Wat?

Injera and wat are at the heart of Ethiopian cuisine. Injera is a fermented flatbread made primarily from teff flour. It’s tangy, bubbly, and uniquely soft, with a spongy texture that soaks up sauces beautifully. Wat (sometimes spelled wot) refers to a family of richly spiced Ethiopian stews, with doro wat (chicken), siga wat (beef), and misir wat (lentils) being among the most beloved.

Together, they form a complete meal served on a large shared platter. The injera lines the bottom, soaking up juices, while additional pieces are rolled or torn to scoop up bites. It’s communal, flavorful, and packed with history. And like many African dishes—such as Yassa chicken from Senegal or Mozambican peri-peri chicken—there’s as much emotion in the food as there is technique.

Essential Ingredients for Authentic Flavor

Let me walk you through the core ingredients I use for both injera and wat. Getting these right makes all the difference.

For Injera:

- Teff flour – I always go for 100% teff when available. It gives authentic flavor and color. If you’re blending flours, keep teff at 50% minimum.

- Water – Filtered is best, especially during fermentation.

- Salt – A pinch is enough, added before cooking.

- Starter culture – I often use a bit of leftover injera batter, but a mix of yeast and vinegar can substitute in a pinch.

For Wat (Doro Wat or Misir Wat):

- Berbere spice – The backbone. A smoky, chili-based Ethiopian spice blend with paprika, ginger, fenugreek, and garlic. I make my own or buy high-quality from specialty stores.

- Niter kibbeh – Clarified butter infused with garlic, ginger, fenugreek, and spices. This brings deep, rich flavor.

- Onions – Lots of them, finely chopped and slow-cooked until they break down into a paste.

- Tomato paste – Adds body and brightness.

- Protein – For doro wat, bone-in chicken legs and thighs. For misir wat, red lentils.

Optional:

- Hard-boiled eggs for doro wat.

- Lime or lemon juice to brighten at the end.

I’ve found that the best wat is built slowly—never rushed—and starts with deeply caramelized onions and berbere gently cooked in niter kibbeh.

Fermenting the Perfect Injera Batter

Making injera is part science, part intuition. And fermentation is key. I start by mixing teff flour and water into a loose batter and letting it sit at room temperature for 2 to 3 days. A tangy smell and light bubbles on top mean it’s working.

Sometimes I use a starter culture from a previous batch. If you’re just starting out, a pinch of yeast and a splash of apple cider vinegar can mimic the natural culture and help fermentation along.

Once the batter bubbles and smells slightly sour, I stir it well and reserve a bit to use as a starter next time. Right before cooking, I add a pinch of salt and dilute the batter with water to get the right consistency—pourable but not watery.

The first few injeras are always test runs. Don’t be discouraged if they break or look uneven. I’ve made hundreds, and even now, the first one often goes to the compost.

Traditional Cooking Timeline (with Prep & Rest)

Below is a timing chart based on my restaurant workflow and home tests. Use it to pace your prep efficiently.

| Task | Duration | Notes |

| Injera fermentation | 48–72 hours | 2 days for mild flavor, 3+ for deeper sourness |

| Batter final prep | 10 minutes | Stirring, salting, and thinning to consistency |

| Cooking injera on skillet | 2 minutes per flatbread | Use nonstick or large crepe pan |

| Onion caramelization for wat | 30–45 minutes | Low and slow for best flavor |

| Cooking wat (chicken or lentil) | 45–60 minutes | Simmer gently after adding all ingredients |

| Assembly & plating | 5–10 minutes | Injera as base, wat spooned on top |

Proper planning helps—start your injera two days before, then make the wat the day of serving for peak flavor and texture.

My Favorite Wat Variations: Meat, Lentils, and Beyond

Over the years, I’ve cooked just about every type of wat you can imagine, and each one brings something unique to the table. The most famous is doro wat, a richly spiced chicken stew. I always use bone-in pieces—legs and thighs—for the deepest flavor. Toward the end of cooking, I tuck in a few hard-boiled eggs, a traditional finishing touch that soaks up the sauce beautifully.

Another favorite is misir wat, a vegan lentil stew made with red lentils, berbere, and niter kibbeh. It’s creamy, comforting, and deeply flavorful when done right. I recommend cooking the onions until they completely break down before adding tomato paste and lentils. A bit of water or vegetable stock keeps the texture smooth.

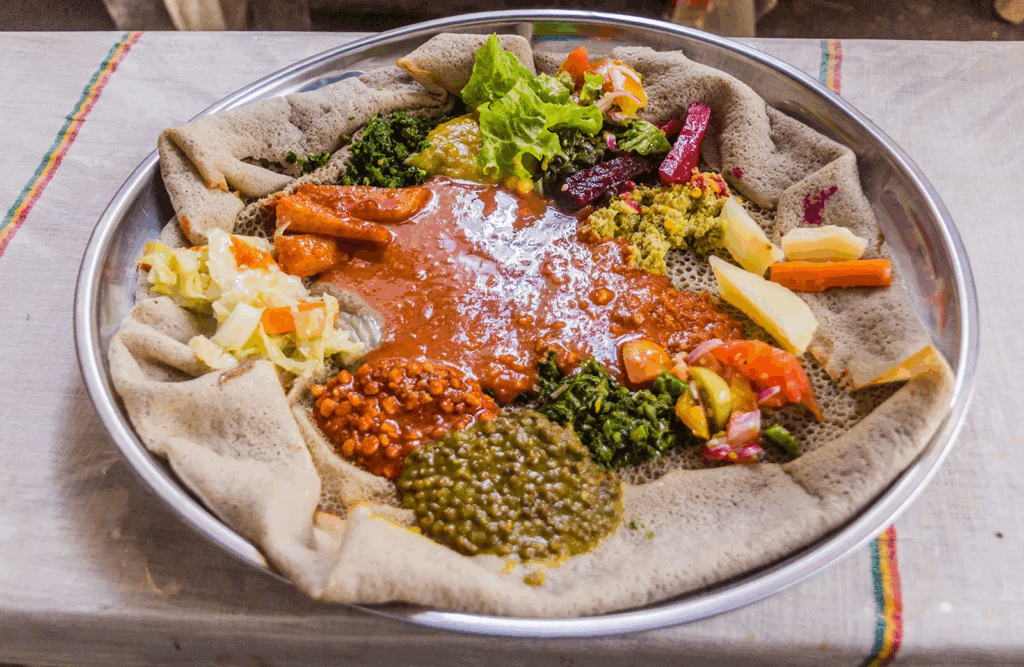

There’s also siga wat, made with beef, and atkilt wat, a vegetable-based stew with cabbage, potatoes, and carrots. I often make a mixed injera platter featuring two or three types of wat alongside sautéed greens and spiced chickpeas. It’s colorful, balanced, and deeply satisfying.

Slow Cooking Wat for Deep Flavor

Wat is the kind of dish that thrives in a slow cooker. I’ve used this method for catering and prep days when I want intense flavor without constant oversight.

Here’s how I do it:

- I start by caramelizing the onions in a skillet until golden and soft. This step is non-negotiable—it’s what gives wat its backbone.

- Then I transfer the onions to the slow cooker and stir in berbere, tomato paste, and niter kibbeh.

- Next goes the protein: chicken for doro wat, lentils for misir wat. I add water or stock just to cover.

- On LOW, I let it go for 5 to 6 hours. On HIGH, 3 hours works well.

What I love about this method is how the flavors develop over time. You can even prep it the night before and reheat gently the next day—wat only gets better with rest.

If you enjoy slow-cooked African stews, you’ll definitely appreciate the robust depth of Chadian shaakalate stew—which also relies on layered aromatics and spice.

Cooking Injera on Different Surfaces

Traditionally, injera is cooked on a large mitad, a flat clay or electric griddle. But at home or in a restaurant kitchen, I’ve used everything from non-stick pans to crepe makers. The goal is even heat and a pan that holds the batter long enough to steam-cook through.

What I’ve found works best:

- A well-seasoned cast-iron skillet for thick, bubbly injera.

- A wide non-stick pan for more delicate textures.

- A countertop crepe griddle if you want consistency and size.

No matter what you use, the technique is the same: pour the batter in a spiral, tilt the pan to spread it evenly, and cover immediately. Injera cooks through from steam—you don’t flip it. When it looks dry and sets on top, it’s done. I always let it cool on a clean towel without stacking, so it doesn’t get soggy.

Vegetarian and Vegan Meal Options with Injera

Ethiopian cuisine is rich with vegan dishes, many of which are traditionally eaten during fasting periods. When I build a vegan injera platter, here’s what I often include:

- Misir wat (red lentil stew)

- Atkilt wat (cabbage, carrot, and potato medley)

- Gomen (braised collard greens with garlic and onion)

- Shiro wat (spiced chickpea flour stew)

- Fosolia (green beans and carrots sautéed with niter kibbeh)

- Salata (fresh chopped salad with lemon dressing)

This kind of platter is vibrant, packed with flavor, and balanced in texture. It’s also naturally gluten-free if you use 100% teff injera. I’ve served it at many events where guests didn’t miss the meat at all.

And if you’re looking for something fiery to contrast these soft and comforting dishes, serve a few bites of Mozambican peri-peri chicken (вставить ссылку) on the side. The heat pairs surprisingly well with mild lentils and fermented bread.

Drink and Dessert Pairings for Injera and Wat

Over the years, I’ve learned that the right beverage and dessert can elevate the injera and wat experience. Because wat dishes are often spiced and rich, you need something refreshing to balance the meal.

My favorite drink pairings include:

- Tej – a traditional Ethiopian honey wine. It’s semi-sweet with a floral aroma and a bit of funk that cuts through spice. If you can find it or make it, serve it slightly chilled.

- Dry white wine – like a crisp Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio. These work well with spicy wat, especially doro wat.

- Sparkling water or lemon soda – great for a non-alcoholic option. Even lightly brewed hibiscus tea with mint complements the heat.

For dessert, you want to keep things simple and clean:

- Fresh mango or pineapple slices with lime zest

- Cardamom-spiced rice pudding made with coconut milk

- Honey-soaked semolina cake (like basbousa, if you’re doing a fusion approach)

I always recommend ending with something cooling and bright to reset the palate. That’s especially true if you served your guests something bold like Yassa chicken from Senegal earlier in the evening.

Storing and Reheating Injera and Wat

As someone who meal preps frequently, I’ve tested multiple ways to store injera and wat. Both hold up well with the right handling.

For injera, let it cool fully, then wrap it in parchment paper or clean kitchen cloth and place it in an airtight bag or container. Keep it in the fridge for 3–4 days or freeze for up to 2 months. When reheating, I prefer using a covered pan with a splash of water on low heat—it keeps the texture soft. You can also microwave it wrapped in a damp paper towel.

For wat, store it in an airtight container with the sauce and protein together. It keeps well in the fridge for up to 5 days. Reheat gently on the stove over low heat. Avoid boiling—this can break the emulsion and dry out the meat. I find misir wat and shiro wat reheat especially well, almost improving in flavor the next day.

Wat also makes an excellent base for leftovers. I’ve used it as a sandwich filling, stirred into rice, or even as a base for shakshuka-style baked eggs.

The Texture Science Behind Injera

I get a lot of questions from fellow chefs about how injera gets its unique texture. It’s all about fermentation and surface cooking.

Teff contains very little gluten, which means it doesn’t stretch like wheat-based breads. Instead, the fermentation process produces lactic acid and CO₂, creating a sour tang and airy pockets. That’s what gives injera its signature sponge-like feel.

When you cook it, the batter spreads into a thin layer that sets quickly on a hot surface. Steam from the bottom rises through the tiny bubbles, forming “eyes”—those little holes that trap flavor from the wat.

What affects texture:

- Fermentation time – longer fermentation = more sour, more bubbles

- Water ratio – thinner batter creates more delicate holes

- Heat control – medium-high heat ensures even steaming without burning

After years of trial and error, I can say: never rush the fermentation. That tangy depth is what makes injera memorable.

Ethiopian Dining Etiquette and Cultural Context

Serving injera and wat isn’t just about taste—it’s about tradition and respect. In Ethiopian homes, meals are shared, not plated individually. The injera is spread out on a large round platter, with different types of wat spooned on top. Everyone eats from the same dish, using their right hand to tear off pieces of injera and scoop up bites.

Some cultural notes I always follow when I serve it in restaurants or homes:

- Right hand only – this is standard etiquette for eating with injera.

- No utensils – everything is scooped with the injera itself.

- Gursha – the act of feeding someone a bite by hand. It’s a gesture of love and respect.

- Leave the base – the injera lining the bottom of the platter soaks up all the juices. It’s often eaten last, like the grand finale.

I always explain these customs to guests, especially if they’re new to the cuisine. It turns the meal into an experience, not just dinner.

Common Mistakes I’ve Learned to Avoid (So You Don’t Have To)

When I first started working with Ethiopian food, I made every mistake in the book. Luckily, mistakes are teachers—and here’s what I’ve learned the hard way:

Undercooking the onions in wat is the biggest error. They need to be fully broken down into a jammy base before anything else goes in. Don’t rush this; it can take up to 45 minutes.

Not fermenting the injera batter long enough leads to bland, flat bread. You need 48–72 hours minimum for depth of flavor. If you want to speed it up, use a bit of sourdough starter or yeast, but still give it time.

Cooking injera on low heat results in gummy, undercooked rounds. High heat and a quick lid to trap steam are essential. Don’t flip it—injera cooks only on one side.

Using the wrong pan can ruin everything. Non-stick or cast-iron are ideal; thin steel or aluminum tends to burn or stick.

If you avoid these pitfalls, even your first attempt can come out beautifully.

Beginner Tips: Your First Injera and Wat Made Simple

If you’re new to Ethiopian cooking, here’s how I coach home cooks:

- Start with misir wat (lentils). It’s forgiving, fast, and delicious. Red lentils cook quickly and absorb flavors well.

- Buy pre-made niter kibbeh or make a simplified version with clarified butter, garlic, ginger, and cardamom. Don’t skip it—it makes a big difference.

- Use a mix of teff and wheat flour for your first injera batch. A 50/50 ratio gives structure while you learn to work with batter.

- Practice pouring the batter cold into a hot pan and swirling just once. Let the bubbles rise, then cover and steam.

And most of all: enjoy the process. Ethiopian food is all about sharing, richness, and community. It’s okay if your first injera looks odd. Mine certainly did.

Fusion Flavors: Creative Takes That Still Respect Tradition

Once you’ve mastered the basics, I always encourage a little creativity. Here are some fusion variations I’ve tested in my own kitchen:

- Injera quesadillas – Use leftover injera to wrap lentils and cheese, then lightly grill until crisp. It’s a hit with kids and casual diners.

- Wat lasagna – I layered misir wat, sautéed greens, and injera sheets in a casserole dish, then baked it. The tanginess replaces tomato sauce beautifully.

- Shiro tacos – Spoon spicy chickpea stew into mini injera rounds or flatbreads with pickled onions and herbs.

- Peri-peri chicken over injera – This combo of bold flavors is incredible. Try it with Mozambican peri-peri chicken (вставить ссылку) for a cross-regional feast.

These ideas bring Ethiopian elements into familiar formats while keeping the core flavors intact. Great for restaurant menus or impressing adventurous guests.

Cooking Method Comparison: What Works Best

After testing injera and wat using all major cooking methods in my chef’s kitchen, here’s my breakdown:

| Dish | Method | Prep Time | Cook Time | Best For | Notes |

| Injera | Stovetop | 5 min | 2 min per | Traditional home cooking | Needs high heat and lid for steaming |

| Injera | Oven (griddle) | 5 min | 2 min per | Large batches | Electric mitad or crepe maker works great |

| Wat | Stovetop | 20 min | 60 min | Best flavor development | Caramelizing onions and layering spices |

| Wat | Slow cooker | 30 min | 4–6 hrs | Set-it-and-forget-it meals | Pre-cook onions and spices before slow cooking |

| Wat | Microwave | 10 min | 20 min | Leftover reheating only | Not suitable for first-time cooking |

| Wat | Oven braise | 30 min | 1.5 hrs | Large-batch beef or chicken | Deep flavor, but requires heavy cookware |

Use this as a flexible guide. I personally love stovetop wat and electric griddle injera for balance between authenticity and efficiency.

What’s the difference between teff injera and mixed-flour injera?

On my own experience, 100% teff injera gives you the most authentic taste—nutty, sour, earthy—but it’s also more delicate and tricky to cook. Mixed-flour versions (teff plus wheat or barley) hold together better and are easier for beginners. I often recommend starting with a 50/50 blend before going full teff.

FAQ

How do I know when the injera batter is ready?

When it smells lightly sour, bubbles form on the surface, and the batter jiggles when you stir it—that’s your sign. I’ve found that 48 to 72 hours at room temperature usually gets it just right. If it smells off (like rotten eggs), toss it and start fresh.

Can I make injera without fermentation?

I’ve tested quick versions with yeast and vinegar for same-day injera. It works in a pinch, but the flavor is flatter, more like a sourdough crepe. For a true Ethiopian profile, fermentation is non-negotiable. You just can’t fake that depth.

What is berbere and can I substitute it?

Berbere is a spice blend unique to Ethiopian cuisine—chili, paprika, ginger, garlic, fenugreek, cinnamon, and more. It’s hard to replicate, but if you must, mix smoked paprika, cayenne, allspice, and garlic powder. I’ve done this in emergencies, but store-bought or homemade berbere is best.

Can I make injera gluten-free?

Yes, and it often is by default if you use 100% teff flour. Just make sure your other ingredients (like starter cultures) are also gluten-free. I’ve served it to gluten-sensitive guests many times with zero issues.

Is injera supposed to be sour?

Absolutely. That tangy, fermented flavor is part of its charm. On my first try, I wasn’t sure either—but now I can’t imagine injera without that soft, sour note. It balances the heat and richness of wat perfectly.

Can I use butter instead of niter kibbeh?

Technically, yes, but I’ve tested this side by side, and plain butter just doesn’t deliver the same complexity. If you don’t have time to make niter kibbeh, infuse butter with garlic, ginger, and cardamom. That brings you close.

How do I reheat injera without drying it out?

From my own practice, the best method is a covered skillet with a splash of water over low heat. You can also wrap it in a damp cloth and microwave for 20–30 seconds. Never reheat it uncovered—it dries out fast.

Can I freeze injera?

Definitely. I do this all the time when prepping for catering jobs. Lay pieces flat with parchment in between, freeze them in batches, then thaw and steam or pan-warm before serving. It holds up surprisingly well.

What’s the best protein for wat if I don’t eat chicken?

Beef is traditional in siga wat, but I’ve also had success with lamb shoulder and goat. For plant-based options, try red lentils, chickpeas, or mushrooms. Shiro wat, made from chickpea flour, is one of my favorites.

Why is my wat too thick or too runny?

This comes down to onion-to-liquid balance. I’ve learned that the onions should break down into a thick base before adding stock. If it’s too thin, simmer longer uncovered. If too thick, stir in warm water gradually and keep tasting.

Can I make injera on a regular frying pan?

Yes, and I’ve done it in dozens of home kitchens. Use non-stick or cast iron, heat it well, pour the batter quickly, and cover immediately to steam-cook. Don’t flip it. With practice, you’ll get those signature holes and soft texture.

Do I need special equipment to cook wat?

Nope. A sturdy pot or Dutch oven will do just fine. I cook most wats on the stovetop in heavy-bottom pans. A slow cooker is great if you want a hands-off method, but not required.

What vegetables go well with injera and wat?

I always serve a mix: sautéed collard greens, spiced carrots, stewed cabbage and potatoes. These add color, texture, and balance the spicy or rich wats. I’ve also done pickled beet salad and cucumber tomato salad for brightness.

Can I serve injera with non-Ethiopian dishes?

Yes, and I do this often in fusion meals. Injera works beautifully with chili, hummus, pulled meats, or even breakfast scrambles. I once served it with Caribbean jerk chicken—it was an unexpected hit. Try pairing with Yassa chicken or peri-peri chicken —you’d be surprised how well it works.