How to Make Fufu Step by Step – Real Guide to This West African Staple

I’ve prepared fufu in upscale restaurants and rural kitchens, using everything from traditional mortars to food processors. And no matter where I make it, the response is the same—it brings people together. This is my personal, professional breakdown of how to make fufu from scratch and through modern methods, from cassava to plantain to pounded yam. Let’s get into it.

- What Is Fufu and Why It Matters

- Core Ingredients for Traditional Fufu

- Texture and Cooking Times – Quick Table Guide

- Classic Stovetop Method – My Personal Go-To

- Baking Fufu in the Oven – A Surprising Method That Works

- Microwave Fufu – Fast but Requires Precision

- Slow Cooker Fufu – Unconventional but Practical

- Creative Fufu Variations That Bring a Twist

- Serving Fufu with the Right Soups and Sides

- How to Store and Reheat Fufu Without Losing Texture

- Common Mistakes People Make with Fufu

- Nutritional Breakdown and Calorie Table

- Creative Plating and Modern Presentation Ideas

- Making Fufu Kid-Friendly or Guest-Appropriate

- Super Fast Version Using Just Flour and Boiling Water

- Experimental Fusion: Fufu Gnocchi with Pepper Sauce

- FAQ – Your Fufu Questions Answered

What Is Fufu and Why It Matters

Fufu is a smooth, stretchy dough-like staple made by boiling and pounding starchy root vegetables—most commonly cassava, yam, cocoyam, or plantain. It’s served as a neutral, soft accompaniment to bold-flavored soups, where it’s pinched by hand and dipped into the broth.

It’s popular in Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, and across Central and West Africa, and each region has its favorite version. In Nigeria, for instance, cassava-based fufu is common, while yam fufu or pounded yam is preferred in some parts of the East.

The reason fufu matters is texture—it needs to be smooth, elastic, and not grainy. I always tell new cooks: making fufu is like making a connection with your food. You feel it, shape it, knead it into something comforting and real.

Core Ingredients for Traditional Fufu

Here’s what I keep on hand when preparing fufu from scratch, depending on the style:

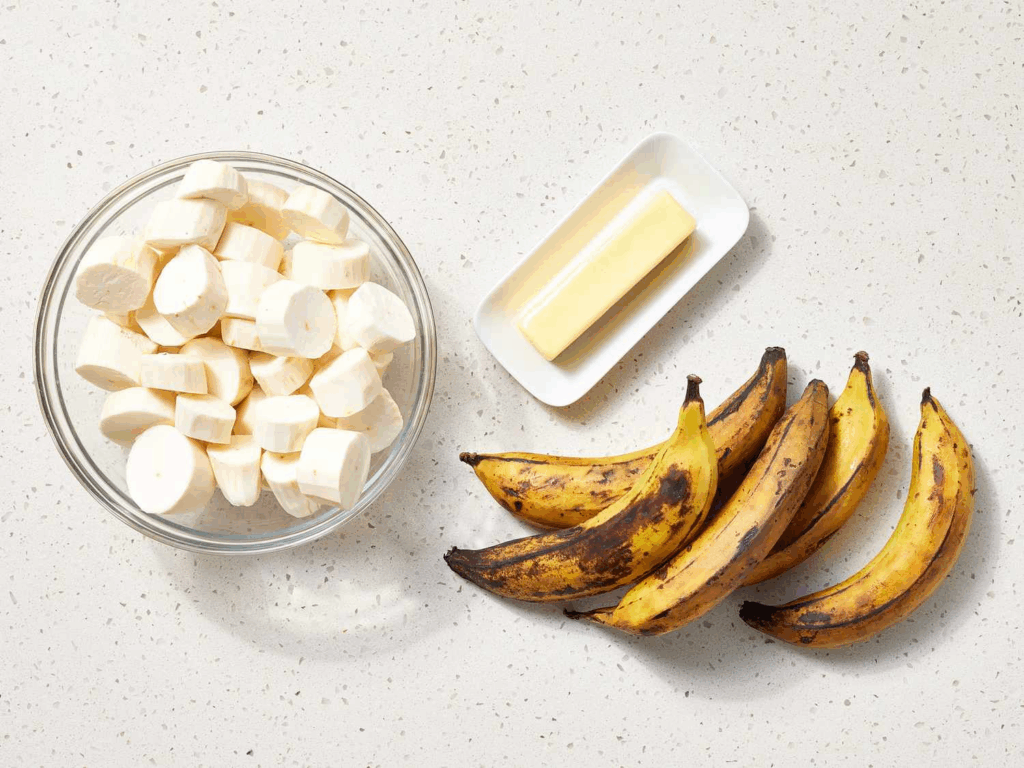

- Cassava (yuca) – peeled, boiled, pounded, or blended

- Yam – fresh African yam (not sweet potato), boiled and pounded

- Plantain – green or semi-ripe, often combined with yam or cassava

- Cocoyam – earthier flavor, used often in Ghana and Cameroon

- Water – for boiling, blending, and texture control

- Optional starch/flour – sometimes used for binding or reheating

When I’m short on fresh ingredients, I reach for high-quality instant fufu flour, especially for yam or cocoyam versions. While not as traditional, they do the job in a busy kitchen.

Texture and Cooking Times – Quick Table Guide

Over the years, I’ve built a chart I refer to for perfect timing and mouthfeel, whether cooking for clients or testing new combos:

| Ingredient Type | Boiling Time | Texture Goal | Chef’s Note |

| Cassava (fresh) | 30–40 min | Soft, mashable | Remove fibrous center before pounding |

| Yam (African) | 25–35 min | Firm yet fluffy | Best for pounding, holds elasticity |

| Plantain (green) | 20–25 min | Slightly sticky, smooth | Peel when raw, boil until pale and soft |

| Cocoyam | 35–45 min | Dense, earthy | Needs extra pounding or blending for smooth finish |

| Instant fufu flour | 10–12 min | Sticky dough | Stir constantly with hot water to avoid lumps |

This table’s saved me countless times when training kitchen staff or running tight prep schedules.

Classic Stovetop Method – My Personal Go-To

When I teach fufu-making classes or prepare it for a traditional dinner, this is the method I fall back on.

Start by peeling and cutting your starchy ingredient (cassava, yam, or plantain). Boil until soft but not waterlogged. Then comes the pounding—either with a wooden mortar and pestle or, in modern kitchens, a stand mixer or food processor.

Once pounded, I transfer the dough into a pot and stir it vigorously over low heat. This part matters. It helps the fufu firm up, lose moisture, and become stretchy. I stir continuously until it pulls away from the pot and becomes smooth to the touch.

“How to cook Egusi soup from Nigeria”, because Egusi is the one I most often serve with classic cassava fufu – it’s the perfect combination of flavors and textures

Baking Fufu in the Oven – A Surprising Method That Works

When I need to make a large batch and keep my stovetop free, I actually turn to the oven. Yes, you can make fufu in the oven—it’s not traditional, but it can be convenient.

Here’s how I do it: I prepare instant yam or cassava fufu flour by mixing it with warm water in a large, heatproof bowl. I stir until smooth and pour the mixture into a greased baking dish. Cover tightly with foil, then bake at 375°F (190°C) for 25–30 minutes.

Halfway through, I stir the fufu with a spatula to help it thicken evenly. When it firms up and pulls slightly from the sides, I know it’s done. I finish by kneading it quickly in the bowl with a wooden spoon or gloved hands.

It’s great for meal prep days when I want smooth results without pot-watching.

Microwave Fufu – Fast but Requires Precision

I’ve made microwave fufu dozens of times, especially when teaching college students or cooking in tight rental kitchens. It works best with instant fufu flour—cassava or plantain.

I start by mixing the flour and hot water in a microwave-safe bowl, using a ratio of about 1 cup flour to 1½ cups water. I microwave on high for 2 minutes, stir thoroughly, then continue in 1-minute bursts, stirring between each round, until it forms a sticky, uniform dough.

Usually after 4–5 minutes total, it’s ready. I let it rest for 2 minutes, then knead it lightly with a wooden spoon. The texture isn’t as deep or chewy as hand-pounded fufu, but when paired with something flavorful like Jollof rice and stew, it complements beautifully. “What is Jollof rice and how to make it” — I had a case when a client at a tasting asked for a duet: microwave fufu and spicy tomato Jollof.

Slow Cooker Fufu – Unconventional but Practical

This one’s rarely seen in traditional kitchens, but I’ve tested it during low-volume prep days and was impressed. It’s especially useful if you want to steam pre-formed fufu balls gently for serving later.

I form the fufu using instant flour and let it cool slightly. Then I wrap each ball in parchment or banana leaves and place them in a slow cooker on low with a shallow layer of water. After 1.5 to 2 hours, they come out warm, soft, and perfect for plating.

This method works great for parties and buffets—I can keep fufu warm and soft for hours without drying it out.

Creative Fufu Variations That Bring a Twist

As a chef, I love experimenting with traditional forms while respecting the roots. Here are a few fufu versions I’ve developed over time:

- Sweet potato and plantain fufu – soft, naturally sweet, perfect with spicy soups

- Oat fufu – gluten-free and fiber-rich, ideal for lighter meals

- Cauliflower fufu – for keto clients; steamed, blended cauliflower thickened with psyllium husk

- Breadfruit fufu – traditional in parts of the Caribbean and West Africa, hearty and nutty

I often pair these with richer soups—like pepper soup made with goat or fish—for contrast. When I served oat fufu with a delicate version of that broth, my guests were surprised how clean and light it felt.

“Traditional recipe for Nigerian pepper soup” is especially appropriate in the alternatives block, since pepper soup often becomes a “test” for non-standard textures.

Serving Fufu with the Right Soups and Sides

Fufu is never served alone—it’s meant to complement something rich, bold, and deeply flavored. In my kitchen, I treat fufu like a neutral base that carries the soul of a dish.

For formal meals, I portion fufu into firm balls and serve it alongside a hot bowl of soup: Egusi, Ogbono, Okra, or pepper soup. Each scoop of fufu is dipped, not chewed, and meant to dissolve slowly on the tongue.

When I cater events, I serve fufu in warm ceramic bowls wrapped lightly in banana leaves—it keeps it soft and gives it a rustic presentation. Sometimes I garnish with a touch of oil or a sprinkle of chopped herbs, especially when plating next to something vibrant like Egusi soup (см. выше встроенную ссылку на статью “How to cook Egusi soup from Nigeria”).

I also pair it with light side salads—like shredded cucumber and onion with a vinegar dressing—to balance heavier meals.

How to Store and Reheat Fufu Without Losing Texture

Fufu is best eaten fresh, but I’ve found smart ways to store and reheat it, especially after large meal prep sessions.

First, always let the fufu cool completely before wrapping. I wrap individual balls in plastic wrap or parchment and refrigerate for up to 3 days. For freezing, I use double layers and store up to 1 month.

To reheat, I steam wrapped portions over boiling water for 10–12 minutes, or microwave on medium heat with a damp paper towel cover. The key is not to dry it out. I’ve also gently kneaded cold fufu in a pan with a few tablespoons of water over low heat—this revives it surprisingly well.

Pro tip: don’t reheat fufu multiple times. Make what you need or store in individual servings.

Common Mistakes People Make with Fufu

I’ve seen beginner cooks (and even some pros) make these mistakes with fufu—and I’ve made them myself.

One is adding too much water during mixing or blending. This leads to sticky, runny fufu that’s hard to knead. I always start with less water and add gradually.

Another is not cooking the dough long enough after pounding or mixing. If it still tastes raw or starchy, it likely needed more time on heat.

Also, I’ve seen cooks forget to remove the fibrous core from cassava before pounding—it creates strings in the final texture. Always cut around that tough center.

Lastly, reheating with high heat often ruins the elasticity. Keep the heat low and be patient. Trust me—it pays off.

Nutritional Breakdown and Calorie Table

Many people ask if fufu is “heavy.” The answer depends on the type and portion. Here’s a quick overview I use for client menus:

| Type of Fufu | Portion Size (1 cup) | Calories (Approx.) | Notes |

| Cassava fufu | 1 cup | 330–350 kcal | High in carbs, low in protein |

| Yam fufu | 1 cup | 250–280 kcal | Slightly less dense, more fibrous |

| Plantain fufu | 1 cup | 220–250 kcal | Lower GI, some natural sweetness |

| Oat fufu | 1 cup | 180–220 kcal | High fiber, good for digestion |

| Instant flour (mixed) | 1 cup | 280–300 kcal | Varies by brand, check label |

| Cauliflower fufu (keto) | 1 cup | 80–100 kcal | Light, low carb, high moisture |

I usually advise guests to pair fufu with protein-rich soups and monitor portion size if they’re on a calorie-conscious plan.

Creative Plating and Modern Presentation Ideas

While fufu is traditionally served as a round scoop or soft mound, I’ve developed a few modern plating techniques that both elevate its appearance and make it more accessible to new diners.

At dinner events, I’ve served mini fufu quenelles using two spoons—placing them neatly beside Egusi or Okra soup in shallow bowls. For tasting menus, I pipe fufu into bite-size dots using a pastry bag—it sounds fancy, but it’s still the same comfort food at heart.

Another elegant touch is wrapping the fufu in steamed banana leaves, which not only keeps it warm but adds aroma and color contrast on the plate.

And for fusion menus, I’ve rolled small fufu portions in toasted sesame or pumpkin seeds before serving with a pepper soup shooter—guests love it for both taste and presentation.

Making Fufu Kid-Friendly or Guest-Appropriate

When I cook for kids or guests unfamiliar with West African cuisine, I slightly tweak texture and temperature to ease them in.

For younger palates, I often use plantain or oat fufu, which are naturally softer and less dense. I keep it slightly looser in consistency and pair it with mild okra or vegetable soup.

To introduce fufu to guests, I serve small portions with dipping bowls of broth, letting them explore without pressure. Once, I hosted a private tasting where I served mini fufu with pepper soup and Egusi side by side—it became a conversation piece instantly.

Texture matters. People new to fufu sometimes hesitate, so I always prepare it ultra-smooth and warm—comfort makes the first impression.

Super Fast Version Using Just Flour and Boiling Water

On days when I’m short on time or energy (yes, chefs have those too), I turn to this fast, 10-minute method using instant fufu flour or yam flour.

I boil water, pour in the flour slowly while stirring constantly, and switch to a flat wooden spatula as the mixture thickens. It comes together quickly—just keep stirring in circular and folding motions until it forms a sticky dough that pulls from the pot.

The trick I’ve found is to let it rest covered for 2–3 minutes, then knead lightly. That resting phase helps set the stretch and make it smooth.

This version won’t have the depth of traditionally pounded fufu, but paired with a strong soup like Jollof-inspired tomato stew or Egusi, it more than holds its own.

Experimental Fusion: Fufu Gnocchi with Pepper Sauce

Here’s one I developed for a West African-Italian fusion menu: fufu gnocchi. Yes, it sounds wild—but it works. I use plantain or yam fufu, let it cool, then form small gnocchi-style pillows and roll them in a bit of yam flour.

I poach them gently in salted water until they float, then sauté briefly in palm oil and serve with a pepper-spiced tomato reduction—like a cross between pepper soup and arrabbiata sauce.

Garnish with basil and shaved cheese, and what you have is a plate that surprises people—but still tells the story of West African flavor. It’s become one of my signature restaurant dishes when I want to challenge expectations.

FAQ – Your Fufu Questions Answered

Can I make fufu without any special equipment?

Yes, and I’ve done it in some of the most basic kitchens. You just need a sturdy pot, a strong wooden spatula, and patience. If you don’t have a mortar and pestle, a stand mixer or food processor works well for pounding.

What’s the best type of fufu for beginners?

I usually recommend plantain or yam fufu for first-timers—they’re softer, naturally smooth, and easier to work with. Cassava fufu is delicious but can be tricky with its fibrous texture.

Can I mix different starches together?

Absolutely. In fact, I often do this in my kitchen. I love combining plantain and cassava or yam and cocoyam for a more layered flavor. Just adjust water ratios carefully, since each starch absorbs differently.

How long can fufu sit out at room temperature?

In my experience, 2–3 hours is the safe range. After that, the texture changes and it can become sticky or develop a sour smell. For events, I keep it in a covered warmer or wrap it in banana leaves and foil.

Why is my fufu lumpy?

It usually means the water was too hot or not stirred vigorously enough. I’ve learned to add flour slowly and stir constantly, especially when using instant powders. And never stop stirring until it’s fully elastic.

Can I make fufu in advance?

Yes—and I often do. I portion it, wrap tightly, and refrigerate or freeze. The key is gentle reheating—steam or microwave with moisture. Don’t overdo it, or it’ll become dry and rubbery.

Is fufu gluten-free?

Most traditional fufus are naturally gluten-free, especially those made from cassava, yam, or plantain. I’ve served it to clients with gluten intolerance without any issue—just avoid wheat-based fufu blends.

Can kids eat fufu?

Definitely. I make softer versions with less heat in the soup, like okra or egusi with oat fufu. It’s nutritious and easy to swallow—just introduce it gradually and make sure it’s warm and smooth.

What’s the best soup to pair with fufu?

On my table, fufu meets Egusi soup more often than anything else—it’s the gold standard. But I also love serving it with pepper soup or ogbono when I want something lighter. It depends on mood and protein choice.

Can I add spices or herbs to fufu itself?

I’ve experimented with this for fusion dishes—like adding turmeric, ginger, or even fresh thyme to oat fufu. It’s not traditional, but it works well with mild stews. Keep it subtle though—you don’t want to compete with the soup.

What does properly cooked fufu feel like?

It should be smooth, elastic, and soft—like a warm dough that pulls when stretched. I test by pressing the back of a spoon into the surface—it should spring back without sticking.

Why does my fufu smell sour?

That usually happens if cassava was fermented too long or if the dough sat out too long after cooking. I always smell and taste during prep—and use fresh roots or flour from a trusted source.

Can I use leftover fufu in another dish?

Yes. I’ve turned day-old fufu into patties, grilled them lightly, or added to soups as dumplings. With a little creativity, leftovers become something new.

Is it okay to serve fufu with non-African dishes?

I’ve done it many times—fufu with chili, stews, even curry. Think of it like mashed potato with more body. Just make sure it’s balanced—the fufu is neutral, so it needs strong sauces.

How do I keep fufu soft for guests during a long dinner?

I wrap portions in foil and place them in a covered pot with hot water (not boiling). It keeps them warm and supple for over an hour. For service, I unwrap just before plating—clean, moist, perfect.